Rebuffing The Feminists: On Sexual Harassment & Objectifying Women

A Partial Defence of The OxShag

After criticism concerning its data acquisition policy, many students have been quick to condemn what The OxShag is alleged to embody: The sexual objectification of women. According to their feminist reasoning the website encouraged men to think of women for their sexual value and nothing else: `[L]ike a catalogue of sex toys to pick and choose from`. Moreover, it is argued the website would have facilitated sexual harassment, and created an unsafe atmosphere for women. I contend the first argument is incapable of seriously condemning The OxShag, and the second argument only goes through on a ridiculous conception of what sexual harassment is, which would make illegal all crude flirting if applied consistently. Moreover, I show how the reaction to The OxShag is totemic of modern feminism and its inherent enmity towards individual freedom. Ultimately, I maintain The OxShag has been condemned beyond any sense of proportion, and rather than being upset about its misdemeanours, we should in fact be far more worried about the illiberal values underlying the feminist overreaction to it.

On Facilitating The Sexual Objectification of Women

What does it mean to objectify a woman? I am willing to accept this definition of objectification: `as the seeing and/or treating a person, usually a woman, as an object`. Given the crucial word in this definition is `object` it warrants definition too. I take the term object to refer to any permanently unconscious thing. Sexually objectifying someone then is to view them entirely or predominantly for their sexual body parts (as opposed to for their consciously developed attributes) and/or to treat them as a tool to your sexual purposes. The feminist philosopher Sandra Bartky contends objectifying women involves failing to adequately acknowledge them for their personality and mind, which then leads women to place far too much concern on their bodies, which is thus to the detriment of their wellbeing. The means through which objectification has this effect includes women feeling they need to wear make-up, conduct skin care, dress up for occasions, conform to particular body standards (Bartky’s `tyranny of slenderness`), and behave in certain feminine ways. Under the patriarchy women become narcissistic as they are continually infatuated with their bodies.

I take the sexual objectification of women per se to be non-problematic, as do the prominent feminists Janet Radcliffe Richards and Martha Nussbaum. I follow Murray Rothbard when he insightfully writes:

`Woman as “sex objects”? Of course they are sex objects and, praise the Lord, they always will be. (Just as men, of course, are sex objects to women.) As for the wolf whistles, it is impossible for any meaningful relationship to be established on the street or by looking at ads, and so in these roles women properly remain solely as sex objects. When deeper relationships are established between men and women, they each become more than sex objects to each other; they each hopefully become love objects as well.`

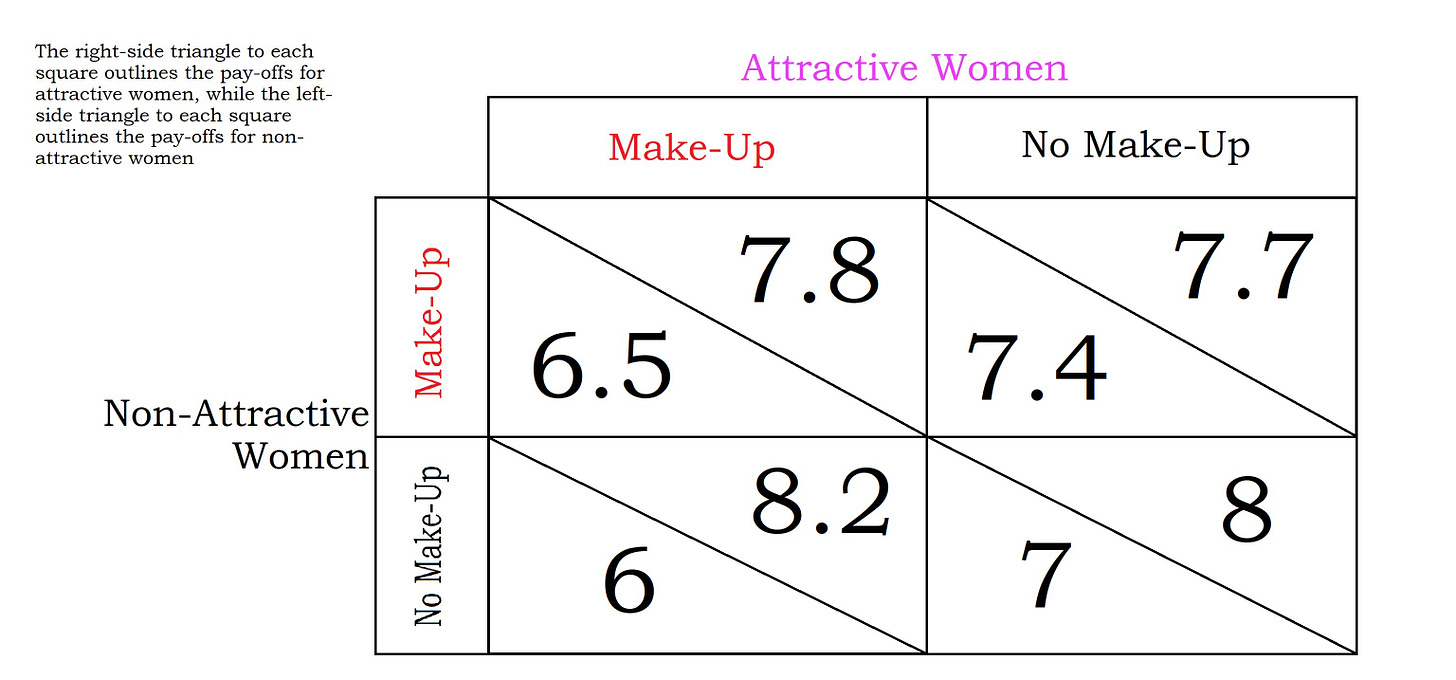

There is nothing wrong in viewing some women exclusively for their aesthetic or sex appeal, as men do when watching advertising, attending beauty contests, and looking at attractive women on the street. Now I concede many women may be made worse off due to this sexual objectification. Perhaps in a world where men did not gravitate towards women who were attractive and made-up, either for romantic, sexual, or aesthetic purposes (some men stay in the company of females simply because they enjoy viewing them), the average woman would be better off. This would be true as all of their time spent dieting, doing make-up and choosing dresses (for men), would not have to be done, yet average male attention would remain constant. Of course, the losers would be attractive women, and those who can make excellent use of make-up, as they would see reduced male attention, which may have been of greater value to them than the cost of dieting and make-up etc. (which, of course, is almost nil for naturally attractive women). Perhaps this is why the most extreme feminists are often the least attractive, having the most to gain from the end of sexual objectification. Nonetheless I suspect some feminists would maintain both attractive and non-attractive women would benefit if neither had to do make-up (conceived broadly as dieting, dressing-up, and make-up proper) though. Maybe. Nonetheless, I believe feminists are not likely to succeed in getting all women to go without make-up though, because it is an unstable condition, which both sets of women have an incentive to defect from. Assuming make-up has a greater effect on the non-attractive, they will experience the greatest gain from any defection from not wearing any make-up: A classic prisoner’s dilemma. Great news for many men.

To my mind though it is irrelevant men, via their sexual objectification of women, make some women, the average woman, or most women worse off relative to its absence. We all make those who smell, are nudists, or have untidy houses, worse off via our conformist attitudes, which reduces their opportunities, or makes them go to great lengths in washing, buying clothes, and cleaning to interact with most of us. Yet I doubt many would argue we have behaved impermissibly in using our attitudes to embarrass them into conforming to our standards, even if they are made worse off. By analogy then, men objectifying women into looking a certain way, even if it makes many worse off, is not impermissible either. How far would I be willing to permit social pressure of this sort create conformism? I don’t know, but I think Mill would be worried already.

Now it could be argued because sexual objectification ensures women have to conform to male beauty standards, they are made unfree, and given people should not be made unfree, sexual objectification should not be practised. This appears to be Bartky’s argument. This does not hold water though: A high social cost being attached to not engaging an activity does not mean when it is given into the individual is unfree. The smelly man having to wash, if he wants to interact for long with people at a party, is not made unfree by the social pressure making him do so. Analogously, women having to wear make-up and conform to male beauty standards, if they want more male attention at parties, are not made unfree by the social pressure exerted upon them. This argument is really nothing more than the former made up with the blusher of freedom to hide its ugliness. Ick.

Now some (deontologists) may still simply maintain it is wrong to think of women in exclusively sexual terms. A Muslim woman quoted in The Cherwell recently said `The thought of people having seen my name and imagined me in a sexually compromising position has left me feeling deeply violated`. Given The OxShag has facilitated this thinking, then perhaps it can be condemned too? This is absurd. If even a mildly attractive woman spends only a moderate amount of time with a man (or should I say boy here?) there is a very good chance he is going to use her image to create many `sexually compromising position[s]` within his mind, particularly at night. Even a prolonged glance at someone in the street may do. Are we really supposed to think sexual fantasizing is violating? Are we supposed to ask its participants permission to think about them? Clearly not. I think we have moved on since Matthew 5:27.

We have now established there is nothing wrong with the sexual objectification of women per se, or indeed with the sexual objectification of women and the effects outlined on them. Thus, insofar as The OxShag has increased the sexual objectification of women, and promoted the outlined effects, it has not done anything wrong. Nonetheless, the discussion cannot stop here, for The OxShag would have facilitated casual sex, which is to facilitate much more than just the sexual objectification of women, and the outlined effects.

On Facilitating Casual Sex

In an article of this size, I cannot properly explain why I believe casual sex to be generally bad, nonetheless, I will contend it is generally bad because it is imprudent i.e. because it is against your long term interests. Jordon Peterson among others would make this type of case – and please note its contingency. Now I think it can be argued The OxShag would have encouraged this type of bad behaviour, indeed the business model would not work without doing so. Is this reason to condemn the website as strongly as some have done (disregarding the privacy concerns I have dealt with)?

No. Individuals in nightclubs will regularly ask whether someone wants to go home with them, with all the implications, and the student community does not condemn that. Of course, this is because many have no issue with casual sex, in which case how can they have an issue with The OxShag facilitating it. And even for those who do have an issue with casual sex, the level of hate The OxShag has received I suspect is disproportionate to the casual sex it could have facilitated, relative to the criticism they make of each individual who engages in the practise. And if someone in a club told a woman that guy over there would like to `have his way with you`, I doubt we would (seriously) condemn the messenger, so why should The OxShag be (seriously) condemned if it sent you an email relaying the same information (as would have been the case with their opt-in system).

Moreover, I think it can even be argued an individual facilitating imprudent behaviour (which is where the badness of casual sex springs from) is doing nothing wrong at all. If an off-license owner carries on selling alcohol to a mild drunk (and he is the only alcohol seller in the village etc.), knowing it is against this man’s best interests, I don’t think many of us would say he commits any wrong. By analogy then, how would The OxShag have wronged anyone by facilitating imprudent behaviour too. To my mind what this shows is businesses do not have any (direct) responsibility for their customers’ wellbeing. Or are we really going to say the burger van man wrongs the obese guy who he sells an extra-large burger too. It may be commendable to not sell the extra-large burger, but it cannot be wrong to do so.

In summary, it should be clear The OxShag would have been doing nothing wrong in facilitating generally bad casual sex, or indeed the sexual objectification of women in the ways I have outlined. Having settled these issues (at least to my contentment) we can now move onto the second argument against The OxShag, which is it would have promoted sexual harassment and an unsafe environment for women. Before I proceed to deal with these issues, it is first necessary to outline what The OxShagT was proposing to do with the matching information it may have received.

On Facilitating The Sexual Harassment of Women

The original proposal involved individuals selecting twenty people they would like to shag from the database of all Oxford University email addresses. If there were any matches, the participants to these matches would be notified, and asked to pay £1 for the information, which would be released on Valentine’s Day. After the change to the opt-in system, it was the case someone who was selected from among the twenty would be sent a generic email asking them to sign-up, given they had been selected. If they did, then the preceding selection process would apply.

Many have said this would have allowed for sexual harassment, two quotes, presumably from Oxford students, are illustrative. The first asserts The OxShag `will result in sexual harassment on behalf of some desperate creep who browsed that database for potential shags`. The second states `it’s revealing that the person who created oxshag thinks the main problem was the data protection issue and not the literal nightmare of the unsolicited sexual harassment it could’ve/has caused.`

Let us consider the two ways in which people would have been “harassed”. First, on the opt-in system someone may have received an email stating either someone has selected you via The OxShag, why not sign up, or more crudely, someone wants to shag you. This is entirely analogous to someone coming up to a woman at a nightclub and saying someone wants to have his way with you. This is clearly not sexual harassment, or if it is, it is largely unproblematic sexual harassment, albeit crude. Now The OxShag’s original plan is even less problematic. It would simply have involved, after someone purchased the information, an email from one half of the match to the other, saying essentially the following: `I hear via The OxShag you are up for a bit of rumpy pumpy with me, would you care to meet at 7pm at X?` How can this be sexual harassment, both parties have explicitly made clear they want to be contacted by the other for sexual purposes. Even by the draconian legislation we will soon be discussing, it is certainly not.

On Sexual Harassment Today & Its Moral Permissibility

Nonetheless, I think the aforementioned comments are revealing of the sad world in which we now live. For the conception of sexual harassment these students have implicitly adopted is that adopted in legislation, namely, the 2010 Equality Act. The following is extracted from that act:

`Other Prohibited Conduct - Harassment

` (1) A person (A) harasses another (B) if—

(a) A engages in unwanted conduct related to a relevant protected characteristic [e.g. sex or sexual orientation], and

(b) the conduct has the purpose or effect of— (i) violating B’s dignity, or (ii) creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for B.

(2) A also harasses B if— (a) A engages in unwanted conduct of a sexual nature, and (b) the conduct has the purpose or effect referred to in subsection (1)(b).

(4) In deciding whether conduct has the effect referred to in subsection (1)(b), each of the following must be taken into account—

(a) the perception of B;

(b) the other circumstances of the case;

(c) whether it is reasonable for the conduct to have that effect.`

I think from these clauses it could be concluded saying something along the lines of `I really want to shag you` could be considered sexual harassment which is prohibited. For it could be argued it violates the dignity of the woman to be objectified in this way. A crucial issue with this legislation is the term dignity is not defined within it. What is astounding though is harassment is in part determined by `the perception of B`, which appears to give carte blanch to accusers. To my mind, if this legislation were strictly enforced, many of the freedoms we enjoy today would have to be prohibited. Consider this example.

A man sees a woman at a bar and proceeds with the following crude pick-up line (taken from a joke book): `If you were a car door, I’d slam you all night long`. Now imagine an uptight feminist rebuffs this man and argues this is sexual harassment – could she succeed in doing so? Let us go through the clauses. Well, it meets 1a), as the conduct is unwanted and relates to her sex, and it meets 1bi) and 1bii) too. For as per clause 4a), it is down to the perception of the allegedly harassed as to whether she feels her `dignity` is violated, or she is `degraded`, `intimidated`, or even `offended` (which basically builds clause 4a) into 1b)). How does this pick-up line not constitute sexual harassment, and thus prohibited conduct? This legislation, if strictly enforced, appears to warrant classifying crude pick-up lines and lewd flirting as sexual harassment, thus making them prohibited conduct. This is ridiculous. Sexual harassment (i.e. crude behaviour) should be ostracized, not prohibited by law.

Perhaps some of my readers think I am being hysterical. I thought so initially. However, various organisations I have investigated have concurred with my judgement. Take Rape Crisis England & Wales who classify the following as among sexual harassment: `Sexual comments or noises, such as wolfwhistling or catcalling; Leering, staring and suggestive looks. This can include looking someone up and down; Sexual innuendoes or suggestive comments; Sending emails or texts with sexual content; Unwanted sexual advances or flirting`. Of course, the issue with the last point is a man does not know whether the sexual advance is wanted or not until he has already made his move! This government report should leave you without doubt `sexual jokes, stares or looks, and sexual comments` are sexual harassment.

Now I think the reason why the crude behaviour I have outlined is not prohibited, outside of the work environment, is because of clause 4c) (although as various law firms make clear sexual harassment allegations may even be brought up concerning `social work events outside usual working hours`). Today it is still accepted as reasonable for men to make these moves in pubs, bars and other social venues, hence it could be argued the uptight feminist is being unreasonable in coming to her position. This is why the work environment is so hostile to romance today, because it is taken as reasonable by employment tribunals for the uptight feminist to have her opinion. Where individuals spend most of their time, they are now afraid of engaging in flirting because of the constant fear this may be perceived as sexual harassment, and result in them losing their job. This has made the world a worse place. Non-rights invading sexual harassment should not be prohibited at work – it is a blatant invasion of free speech which should never be tolerated. The regulation of sexual harassment at work should be decided by contracts between employer and employee.

And for those concerned with women being continually harassed by male bosses, managers and co-workers, two arguments can be put. First, given women dislike lots of sexual harassment, their supply to firms who permit this behaviour will be lesser, and thus employing them will be more expensive than otherwise, meaning firms will have an incentive to offer contracts ruling out lots of sexual harassment (especially as the pleasure derived from sexual harassment does not add to profits). To attract the greatest supply of labour (and thus the lowest price) profit-maximising firms will adopt sexual harassment policies which are most popular with workers. I suspect this will allow for more sexual harassment than now (to attract a greater supply of men, and, indeed, many women who do not want men to fear approaching them), but curb the excesses which many feminists imagine. And for those firms which allow for all sexual harassment, the pay for women working in them will be higher than otherwise.

Many will question this Beckerian analysis, doubting labour markets are as competitive as I propose. I cannot address this issue of microeconomics here, nonetheless, I would point to the free gym membership, private health insurance and company car which many employees are offered, which would not be without these competitive forces, as evidence markets approach the neoclassical model. Second, Block and Whitehead challenge many progressive feminists still maintaining sexual harassment should be illegal with this ingenious argument. They contend if buying the services of a prostitute is legal, and buying the services of a secretary is legal too, why cannot you buy the services of, i.e. employ, an individual who spends half her time being a prostitute and half her time being a secretary. Clearly if both are legal, any combination of the services should be too. Thus, provided consent is always forthcoming, behaviour which would otherwise be sexual harassment, should be legal. I emphasize here what is legal is not always admirable behaviour. Nonetheless, given sexual harassment can mean simply asking a woman out three or four times, I still do not think it can be condemned per se.

I now wish to return to clause 4c) though and argue it is an incredibly weak provision in protecting individual freedom. Imagine the views of our uptight feminist have become widespread in society, and online dating has emerged as the overwhelming means through which people find romantic and sexual partners, because this ensures both parties agree to any approaches (that is the point of dating apps after all). Offering lewd pick-up lines, or even invitations of the sort, `I think you look absolutely stunning, may I buy you a drink?`, are considered seriously offensive. This is generally believed because it puts the woman on the spot and demonstrates a man has objectified her (and the lewd comments even more so). In this future it would be `reasonable for the conduct to have that effect [i.e. of extreme offense]`, clause 4c) would support this man’s behaviour being sexual harassment. Clause 4b) would push classing the conduct as sexual harassment too, as any appeal to the normal practise of asking individuals out would be mute. All this would make robust the fulfilment of clause 1bii), as the woman could convincingly argue she had been put in a degrading and offensive environment. Flirting would thus count as sexual harassment and therefore be prohibited!

Fortunately, this dystopia is still far away, nonetheless, if the two students I have quoted understood how the opt-in system for The OxShag would have worked, this is the conclusion to which they are driven. For if an email informing you someone would like to shag you is sexual harassment, how is a verbal communication not too. And if one should be prohibited, how can the other not be too. What is so frightening though is that if this attitude of the two students I have mentioned were applied consistently, and became widespread, is existing legislation would make lewd flirting illegal (as clause 4b and 4c would become inadequate blocks). Our sexual and romantic freedom cannot rely on this contingency of social attitudes and practises: The 2010 Equality Act must be repealed. And in the meantime, the views of the two students I have quoted must be opposed (assuming, of course, their objection to sexual harassment implied the use of force to stop it) to ensure we do not end up in the dystopia I have outlined.

On Making Women Feel Unsafe

Having demonstrated why The OxShag should not be condemned for facilitating sexual harassment, which it would have only done under its second-best opt-in scheme anyway, we can now briefly deal with it making women feel unsafe. I suppose it could be argued having a woman being sent an email informing her of the fact she has attracted much sexual interest could make her feel unsafe. Making someone feel unsafe per se cannot be regarded as bad though. Assume the more attractive a woman is the more likely she is to be raped (not implausible I think). Now imagine a very, very, attractive 23 year-old woman, who has been brought up in a nunnery and not left it since she was 12, decides to go to a dance where there are lots of men. At the nunnery she has been told she is just an average looking woman, but she has been told very, very, attractive women are far more likely to be raped. At the dance a fellow nun, who is not so naïve, tells her she is, despite what the other nuns have said, very, very, attractive (and her normal friend confirms this to her). Resultantly this nun is made to feel much more unsafe than before, as she realises, she is more likely to be raped. Has this friend done anything bad or wrong? Clearly not. By analogy then, The OxShag would have not done anything bad or wrong in making women know they are more popular among men, and thus, by assumption, more likely to be raped, assaulted or harassed. Evidently informing someone of the truth is not itself deplorable, indeed it usually ensures the receiver is more prudent, and thus could even be argued to be helpful.

On The OxShag Model

We are now close to bringing these two articles to a close. Nonetheless, I think it is briefly worth discussing exactly how The OxShag would have made its money, sociologically speaking, and which issues it may have overcome. Essentially, when a man decides he wishes for a casual shag, he attributes some benefit to it. In enacting this desire, he only attaches a slight probability to his asking being successful, and this creates an expected benefit for him. This man will then face numerous costs in making his offer e.g. embarrassment in potential rejection, reputational damage, and search costs in finding the girl. For most men the costs outweigh the benefits, thus making such explicit propositions unprofitable, and thus not practised. (Hence most normal men engage in dating, clubbing, or going to alcohol-laden parties to attain their ends).

The ingenuity of The OxShag would have been to nearly eliminate these three costs for men, meaning those at the margin of making explicit propositions, would have found making them profitable. Realising the benefits for many men though would be large enough, The Oxshagger saw he could carve out some of that benefit as his fee (originally £3, then reduced to £1). Now some may argue what The Oxshagger was proposing was not that different from an ordinary dating site. Maybe, but the nous for profit was in realising it was best to create a pool of individuals who had the required thoughts on each other on their mind often. Of course, the major problem with this site would have been an oversubscription of men, as men are around twice as likely to desire sex as women. Nonetheless, given time I am confident the enterprising spirit of The Oxshagger could have mitigated this issue. Such are the virtues of the free market, any end it is given by consumers, however repulsive, will be pursued with approaching the utmost efficiency. Although numerous criticisms have been made of The OxShag I cannot but think many are significantly motivated by a serious dislike of free enterprise, of profit-seeking, and of business generally. For the lewd propositions which would have been facilitated by The OxShag are not at all far away from the suggestions made at nightclubs and drunk parties.

Conclusion

In sum, it is clear the feminist critiques of The OxShag do not hold water. There is nothing necessarily wrong with the sexual objectification of women, and its facilitating of casual sex would have only been as bad as the off-license owner selling gin to a mild drunk. And the “sexual harassment” The OxShag’s opt-in policy would have facilitated would have been no worse than uttering a crude pick-up line either. What should be more worrying is the implicit conception of sexual harassment adopted and alleged to The OxShag, is one which would, if adopted generally, make all crude flirting illegal. Such is the illiberalism of modern feminism it must be opposed with the utmost force, even if that does mean defending the spivs, incels and perverts of this world in the process. This is not an alluring battle to fight, but the preservation of freedom more than warrants the call to arms.