It is widely believed that Robert Nozick fails to justify the minimal state in the first part of Anarchy, State and Utopia. Anarcho-capitalism seems to be the logical conclusion of libertarian theory. Yet a few libertarians have clung onto the idea of the minimal state; one of them is Eric Mack. Mack contends via his anti-paralysis postulate that individual rights must be construed so as to maximally protect their purpose, i.e., ensuring each of us can pursue our own good in our own way. Accordingly, Mack argues taxation must finance the minimal state’s army and police to maximally protect individual rights.

In this endeavour, I will show this implausibly commits Mack to a utilitarianism of rights which is anathema to the deontological foundation of libertarianism. Resultantly, Mack should return to the anarchist fold of his yesteryear to maintain a central element of libertarian theory and reject what Murry Rothbard calls ‘a gang of thieves writ large’, i.e., the wretched state. A crucial concept in this article is the public good, namely, a good which is nonexcludable and nonrivalorous in its consumption, e.g. street lights, public policing or a nuclear deterrent.

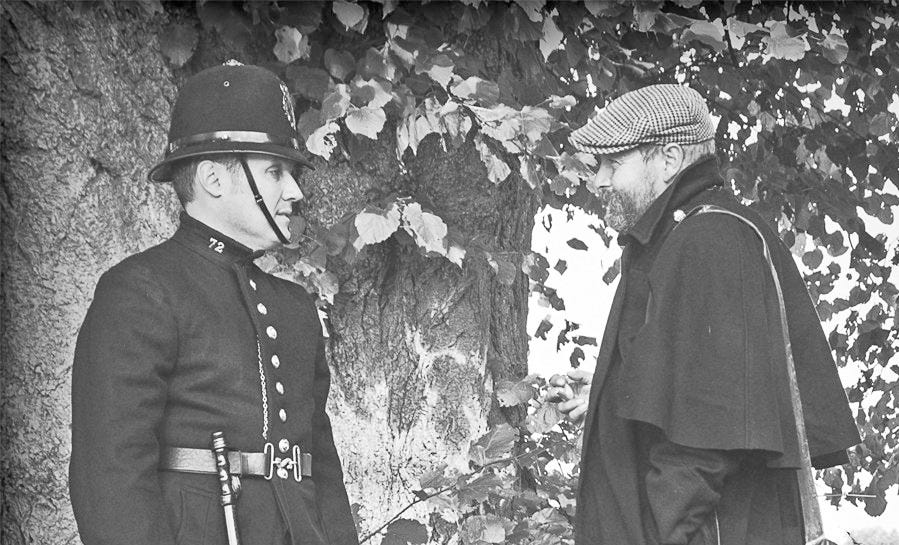

The main empirical contention of Mack’s argument is ‘rights-bearers would be substantially less able to coordinate so as to protect their rights if they are understood to preclude their being required to contribute to the funding of protective services’. Why? This is because in policing an area the benefits of reduced crime go to everyone including to nonpayers, so, rational people do not bother to pay private police because they’ll get the benefit anyway. Everyone does this, and, hence, private polices cannot finance themselves. Now, I think this is questionable. Rothbard and Bruce Benson have raised good arguments for the possibility of the private provision of security, and, Steve Davies has evidenced how private policing in Victorian England such as the Barnett Association reduced crime.

Nevertheless, let us accept Mack’s empirical claim. His central normative contention is the anti-paralysis postulate. Mack summarises it as the requirement: ‘one must avoid specifications of rights that systemically morally preclude individuals from exercising their rights or conducting their lives in ways that a specification of rights is supposed to protect’. Mack gives three examples of where this anti-paralysis postulate is useful outside of the anarchist minarchist debate to show it is not an ad hoc development of libertarianism. Here’s one. Consider a specification of rights where imposing any risk of their violation would be morally impermissible. ‘Rather than enhancing persons’ peaceful enjoyment of their rights, this specification of rights would systemically diminish each person’s sphere of permissible and morally protected actions’.

Obviously, this is against the broad purpose of rights in ensuring each person can pursue their own good in their own way, thus, this specification of rights must be rejected. Now, Mack contends that allowing anarcho-capitalism will result in a greater number of rights violations overall compared to a minimal state its taxation and a resulting reduction in crime. As a result, the anti-paralysis postulate supports ‘a limited attenuation of these rights bearers’ property rights’ permitting taxation to finance policing to ensure each person can better pursue their own good in their own way, i.e., the broad purpose of individual rights. This moral reasoning faces the following problem.

A utilitarianism of rights is the idea that moral theory should dictate not respect for rights, but, rather, the minimisation of rights violations. Bernard Williams offers the thought experiment of Jim and The Indians where the tribal leader asks Jim, a visiting explorer, to either kill one of the tribe or he will kill all of them bar that one (this may be a modification of the original example). Overall, the number of rights violations will be reduced by Jim doing the killing of one. Mack explicitly rejects the verdict Jim should kill the one Indian. He writes: ‘I ought not to kill innocent A even if doing so will prevent Z from killing innocents B and C.’ Given Mack does not want to support a utilitarianism of rights he must reject his anti-paralysis postulate which accepts it, e.g., he must reject taxation, i.e., theft, to reduce down the overall amount of theft, hence, he must jettison his justification for the minimal state that taxes. Again, in other words, if he is not going to permit murder to reduce the overall amount of murder down neither can he justify taxation, i.e., theft, to reduce down the overall amount of theft.

Against this Mack could argue that Jim cannot kill the one Indian because he gets no compensation in the form of reduced rights violations to him because he is dead, thus, this specification of rights doesn’t really fit the purpose of them as allowing each and every one of us, individually considered, to pursue their own good in their own way. Therefore, accepting the anti-paralysis postulate he uses to create the case for the minimal state does not include accepting, contrary my claim, the implausible proposition Jim must kill the Indian, i.e., a fully bodied utilitarianism of rights. However, taxation to finance policing is still okay because everyone gets an outweighing benefit from the minimal state via reduced crime. To be clear: Mack could claim he can have his (plausible) anti-paralysis postulate without a (implausible) utilitarianism of rights. Notice here, the overall reduction in rights violations under the minimal state has to be net advantageous to each person in terms of actual reduced down rights violations too.

The problem with this line of argument is it seriously undermines the power of the minimal state too because many people will claim the actual taxation put upon them will be greater than the actual cost of crime they would otherwise undergo, hence, they cannot be taxed either. Since in many anarchist societies the medium person will not be subject to any crime this could be appealed to by everyone, or, loads of people at least, and, obviously, the actual taxation in excess of this zero sum will mean they are worse off. Thus, the minimal state will need to shrink to a tiny size, or, nonexistence.

To overcome this problem Mack will no doubt fall back on an expected value approach to crime, meaning, the taxation is permissible provided it reduces down on a net analysis (that is including its own imposition) the magnitude of crimes multiplied by their probability for each person. This gets Mack back to supporting a minimal state. The problem then is Jim can kill the Indian which is a clear case of a utilitarianism of rights because the practises of murdering one to stop the murder of twenty reduces down the expected value of being murdered for each person in the population which enables each person to better pursue their own good in their own way. Or, at least, it gets him to a utilitarianism of rights where each person has to get an expected reduction of rights violations out of it, i.e., a partially bodied utilitarianism of rights. (It also forces him to push the fat man off the bridge.)

This embrace may not be such a bad thing, yet, I still strongly errrr against it. Francis Kamm does a decent job at explaining my reticence and Thomas Nagel summaries her thoughts here: ‘but one would thereby be accepting the principle that anyone is legitimately murderable, given the right circumstances [should Jim be allowed to kill an Indian]. This is a subtle but definite alteration in everyone’s moral status.’ This objection to the alteration in moral status comes from the Kantian opposition of people being used as mere means to the ends of others. For this is to deny the ultimacy of personal value which resides in each of us, i.e., our lives being properly directed to our own flourishing. And this Kantian opposition is definitely one that Mack himself accepts in the rest of his extensive work in libertarian theory.

Yet upon reflection that Kantian objection seems to only concern the full-bodied utilitarianism of rights, i.e., where it doesn’t matter if someone has their rights violated to a greater extent provided the overall level of violation is reduced in the population, and, not the partially bodied utilitarianism of rights mentioned. This is because the person is not being used to others ends’ but only his own. Contrary that though the end of the individual is not always the protection of his own rights before everything else, thus, we can say he’s still in some instances being used as mere means to the ends of others in being forced to finance public policing. Imagine I live in Hobbes’s state of nature and my chance of being murdered and tortured is very high; I don’t think this would justify removing me to a desert island where I’d face fewer rights violations overall (including the removal to the desert island), even if my interests weren’t set back, or, only minorly, certainly not against my will. Rights and their practical extent should partially be under the individual’s own jurisdiction.

In sum, the minimal state should be rejected by libertarians if they stand it on Mack’s grounds, because, it implausibly commits them to a utilitarianism of rights. I should note though I don’t think this has to lead to a rejection of the anti-paralysis postulate in full because when dealing with minor pollution or risk there is a riding roughshod concern and not a mere means concern at stake, unlike when taxing people. Indeed, Mack himself recognises this in his ‘Elbow Room for Rights’ in Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy where he writes: ‘[T]his liberty [to incidentally pass a little smoke over your fence] need not extend to malicious (or wanton) minor intrusions’.